Matawai: Place-based Storytelling in Suriname

Pour le moment, ce document n'est disponible qu'en anglais et en espagnol. Si vous souhaitez aider à le traduire en français, nous serions ravis de votre contribution!

The Matawai of Suriname, a community that once felt forgotten by the rest of the world, is breaking ground by using a new open-source geostorytelling app called Terrastories to create an extraordinary repository of traditional knowledge through oral history storytelling. The goal of the work is to ensure that future generations of Matawai will be able to learn about their history, culture, and identity in the way that their people always have: through the words of the elders.

Who are the Matawai Maroons and why is their history so important to them

The Matawai of Suriname, a community that once felt forgotten by the rest of the world, is breaking ground by using a new open-source geostorytelling app to create an extraordinary repository of traditional knowledge through oral history storytelling. The goal of the work is to ensure that future generations of Matawai will be able to learn about their history, culture, and identity in the way that their people always have: through the words of the elders.

The story of the Matawai is one that begins over three centuries ago, when Suriname was a Dutch plantation colony. Rather than endure a cruel and punishing life of captivity on the colony’s coastline plantations, scores of African enslaved peoples took destiny in their own hands and escaped into the dense rainforests of the country’s vast interior. Bands of fugitives fled along the ascending rivers, leading them as far southward as they could. They evaded and battled with Dutch soldiers who sought to recapture them, embarked on raids to liberate others from slavery, and eventually forced the colonial government to sign a peace agreement with them.

Different groups of these formerly escaped slaves established themselves in the center of Suriname’s interior, where their descendants continue to reside today.

The members of these communities, today known as Maroons, proudly describe the first days their ancestors settled in and fought for what is now their traditional homeland, part of their distinctive history.

One of the smallest Maroon groups are the Matawai, who reside along the banks of the Saramacca River in central Suriname. For the Matawai, survival in the rainforest has always depended on an intimate knowledge of their territory, passed down by their ancestors. Place-based stories help them determine where food or resources are located, or where dangers lie hidden. Most importantly, the oral histories reinforce their historical and cultural connection to their homelands, which in turn informs their collective identity and encourages them to protect their environment.

Why did the Matawai start mapping their lands and recording their history

Until a few years ago, the Matawai territory was among the most remote in the country, accessible only by boat or by small aircraft. However, rampant and destructive alluvial gold mining activity, new telephone towers, and the recent creation of a network of roads servicing logging operations and connecting the twenty-one Matawai villages have brought rapid and sweeping changes.

In this changing landscape, younger Matawai are increasingly finding employment in the gold mines or leaving to go work and live a more modern life in the capital city of Paramaribo.

Many Matawai villages have an empty or desolate aura to them, with only a few Matawai continuing to live in a traditional way. The remaining elders frequently lament that the youth seem more interested in their phones than in their history, and have stopped sharing stories with the younger generation. Consequently, the longstanding Matawai oral tradition of sitting around and trading stories of Fositen (referring to the “first times” their ancestors arrived in these lands) risks being lost in time.

To prevent that from happening, the local community-based organization Stichting voor Dorpsontwikkeling Matawai has spent the last few years documenting their storytelling traditions using video recorders and interactive maps. With support from the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), the organization trained a team of interested younger Matawai to record and interview their elders about the numerous named places and historically significant sites throughout their ancestral lands.

To date, the initiative has yielded over 17 hours of video footage about more than 150 historically significant places along the Saramacca River. For a number of the young Matawai involved in the project, it has brought them their first real opportunity to hear about the history of their homelands.

The Matawai elder Josef Dennert, reflected on the project: “… [my] inner wiseman had been sleeping all this time, but then I realized it was not too late. I had to follow them and finally apply my knowledge.”

How this work brought the Matawai to the Smithsonian Archives

The effort to document and preserve the community’s oral histories has led the Matawai to seek out support from a number of institutions—some very far removed from their homelands. In September 2018, Dennert, along with two other Matawai, traveled to Washington, DC to research the papers of Edward C. Green at the Smithsonian Institution. Green, an anthropologist, amassed a collection of field notes, photographs, and audio recordings captured during his time with the Matawai in the early 1970s and recently donated these to the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives. Sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution’s Recovering Voices Program, the three Matawai researchers were able to access these invaluable historical materials for the first time, and were permitted to take back copies to share with the rest of their community. At the end of the experience, basja (traditional leader) and research participant Tina Henkie reflected on the process:

“These anthropologists wrote things down, while my people back then couldn’t write. But they told stories, and then the anthropologists recorded them. And now that the people aren’t with us anymore, we should be able to find the story somewhere. And that is what we’re doing now here at this archive; I try to imagine how my ancestors lived back then. And that gives me a feeling of pride to be a Matawai, because it helps me know my roots.”

The Development of Terrastories

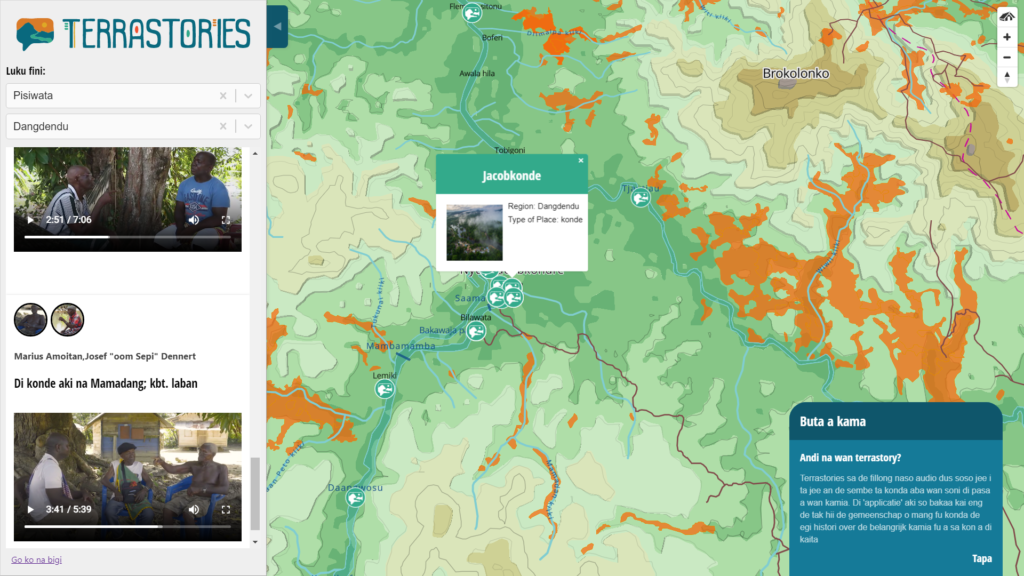

To enable hosting of the recordings of oral histories, and linking of the histories to maps of the ancestral homelands, ACT collaborated with Mapbox, a mapping tech company, and Ruby for Good, a team of volunteer developers, to build a novel geostorytelling application called Terrastories.

The application interface consists of an interactive map and a sidebar with media content and stories. Using a content management system, the Matawai can add important places and stories to maps, and designate the privacy settings of their original content. Terrastories works without internet access, and the code is open-source so that any community in the world can adapt it to map their own place-based storytelling traditions.

Terrastories is an application for communities to map, protect, and share stories about their land. It can be used by individuals or communities who want to connect audio or video content to places on a map. It is designed to be user-friendly and fun to interact with, allowing community members to freely explore without needing any technical background. Learn more: Terrastories: a Tool for Place-Based storytelling

In October 2018, in Paramaribo, the Stichting voor Dorpsontwikkeling Matawai presented a version of Terrastories fully populated with all of the Matawai stories and maps before an audience of Maroon community members, traditional leaders, and Surinamese government officials. The project has spurred a national conversation around recognizing and protecting the Surinamese Maroon culture as intangible cultural heritage.

The Matawai Oral History Mapping Process

As of 2020, the Matawai Oral Histories Mapping Team has completed the following process with the ten villages along the Upper Saramacca River.

Elements:

People: One of the most important aspects guiding this project throughout is the desire and enthusiasm on behalf of the Matawai to pass along their most precious histories to the youth, and ensure that future generations will always have access to that knowledge and understand their roots and where they come from. This desire is founded in a deep appreciation of and pride in their ancestors’ struggle to gain the right to exist as a free people in the rainforest.

Values: Autonomy was key to the success of this project, with the Matawai community-based organization taking the lead in designing the project, introducing the concept and work plan to the community, and identifying elders and knowledge keepers. The NGO involved took a more supportive role and always worked together with Matawai community members, which helped build relationships of trust. In addition, local data ownership was key to this project, especially in relation to the Matawai having the ability to determine who has access to the stories and maps. These values also strongly informed the development of Terrastories.

Technology:

- Large sheets of paper, colored marker pens

- GPS handheld devices (Garmin 64)

- Weather-proof notebooks

- A laptop and backup drives

- Lightweight, portable projectors so that an entire village could review the maps as they were being produced, and watch oral histories videos

- Audio recorder (Zoom H6N)

- Video recorder (Canon Rebel t3i)

- GIS and cartography software: ArcGIS, Mapbox Studio

- Design software: Adobe InDesign

- Video editing software: Adobe Premiere

- Mini-computers which operate as offline servers for Terrastories

Workshop and Trip Resources:

- Boat, fuel and food supplies

- Walking kits, rubber boots, rucksacks, waterproofing etc.

- Printed draft maps for krutus in each of the Matawai villages

As of 2019, the Matawai have recorded over 17 hours of footage featuring 35 community elders, consisting of 150 stories for over 300 places in their ancestral lands.They have also mapped over 700 historically significant place names in their territory, the Saramacca River watershed.

Community Agreements: Led by the community-based organization Stichting voor Dorpsontwikkeling Matawai, the organizations involved in the project come to agreement with and receive permission from the traditional Matawai leadership to begin the project. Each party — Stichting voor Dorpsontwikkeling Matawai, and the Amazon Conservation Team-Suriname (ACT) — come to agreement about their roles and responsibilities.

Sketch Mapping: In 2015, the project starts with krutus (workshops) in the villages during which community members draw on and annotate blank maps of the Saramacca river, using their knowledge of the landscape. A geographer from the ACT team compiles the data into GIS maps using ArcGIS, which serve as the first version of the Matawai ancestral lands maps.

GPS Training and Collecting Knowledge About the Land: Community members, both male and female, are trained by ACT to use handheld GPS (Global Positioning System) units for recording spatial data about land use such as hunting routes/activities, agriculture, or harvesting resources. During this phase, some of the data that was initially drawn on paper maps is captured with greater accuracy using the GPS units.

Field Mapping Expeditions: On two occasions in 2015 and in 2017, mapping teams (composed of Matawai youth, a Matawai elder, and geographers from ACT) travel up and down the Saramacca river for several weeks, using GPS units to map place names for creeks, rapids, islands, former village sites, historical places, natural resource gathering sites, and other places of significance. The ACT team uses the information to improve upon the maps in ArcGIS.

Map Validation: After these data collection phases, ACT geographers use ArcGIS to compile Matawai territory maps, and on several occasions, the Stichting voor Dorpsontwikkeling Matawai organizes krutus where community members provide feedback on the accuracy of the data, mistakes in spelling or naming, and places that have not yet been mapped. A comprehensive ancestral lands map draft is finalized towards the end of 2017.

Recording Oral Histories: During the final phase of mapping, the team starts to record oral histories with elders who are knowledge keepers and familiar with the Matawai histories as narrated to them by their ancestors. From 2017 until 2018, the team is able to record conversations with 35 elders from Matawai villages along the Saramacca river and living in the capital city of Paramaribo.

Designing and Printing Maps: In 2018, ACT finalizes cartographic maps for the Matawai ancestral lands using ArcGIS and Adobe InDesign. These are printed and delivered to each village, where they are often displayed in the kuutu wosoe (meeting halls).

Building Terrastories: ACT geographers collaborate with a volunteer team of developers to populate Terrastories with the Matawai maps and oral histories. To do so, the maps are uploaded to Mapbox Studio and downloaded as map tiles to run offline. The Terrastories application with the Matawai maps and stories are stored on mini-computers that can run offline. On several occasions, the team brings these to the two central Matawai villages of Pusugrunu and Nieuw Jacobkondre and presents the oral histories and maps to the community, public schools, and traditional leadership.

Serving Terrastories Offline: Two mini-computers are equipped with Terrastories and the Matawai content and donated to the public schools in the Matawai villages of Pusugrunu and Nieuw Jacobkondre. The schools are charged with safekeeping the information and administering access while the community continues to figure out permissions for each individual story, led by Stichting voor Dorpsontwikkeling Matawai.

Further reading and viewing:

- Interactive story map: Lands of Freedom: the oral history and cultural heritage of the Matawai Maroons in Suriname - October 10, 2020.

- Feature article, Sabaku - Suriname Airways inflight magazine, Ed. 61: “Matawai: Oral tradition in modern times” - November 2019 - January 2020.

- Methodology guide: Mapping and recording place-based oral histories: a methodology - ACT, June 2019.

- Documentary: “Fosten: A Story about Tradition and Territory (Matawai Oral Histories)” - October 10, 2018.