Since time immemorial, stories have traveled along with humanity as both company and reminders of who we are and where we are from. So is the case of the Jingwei Bird, a traditional Chinese story that crossed the Pacific Ocean with the Chinese diaspora to a new homeland in the United States. Between 1910 and 1940, different hands carved this and other stories and poems into the walls of the detention barracks of the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco, where they have remained since. Now the stories have taken a leap into Explore Terrastories in the hands of The Last Hoisan Poets, Del Sol Quartet and Andi Wong, who share and honor the Chinese collective memory through their creative work.

“If you have to leave home and can’t take anything with you, what do you take? You take stories”, says Andi Wong, who was born in Sacramento in 1961 but has made San Francisco her home since 1988. Her creative journey as an art teacher and advocate has led her to a series of “serendipitous conversations” that later became collaborations and eventually built her path to find the intersection between the Jingwei Bird Story, Angel Island, and her family history.

“This process has been learning about my ancestry and discovering my relationship to the city. Many people in San Francisco don’t know the history of Angel Island, and I always find it kind of strange. It’s the largest natural island in the Bay and an integral part of the city. It was the entry point for most of the people of Chinese American ancestry in the United States”.

Andi’s grandmother was five months pregnant when she arrived in San Francisco and was held, like many other Chinese people, on Angel Island.

“It was a place that was designed to hold immigrants for questioning, and a lot of the more aggressive questioning involved specifically people of Chinese descent. It was pretty much a prison where they would have to go through questions, and they would want you to mess up. As a descendant, you can ask for the interview transcripts and see what happened to your ancestors. I hadn’t seen these transcripts until I started working on this project in 2018.”

Angel Island is now a State Park, and the barracks that used to be the detention center remain as testimonies of the story of immigration and discrimination, hopes and fears written in words that were carved into every inch of its walls. According to Andi, the immigrants that were held there carved sad, angry, longing, dreaming poetry or “everything you could imagine from an immigrant coming to a new country and all of a sudden held in prison”. Their carving references to classical poetry or writing of their own.

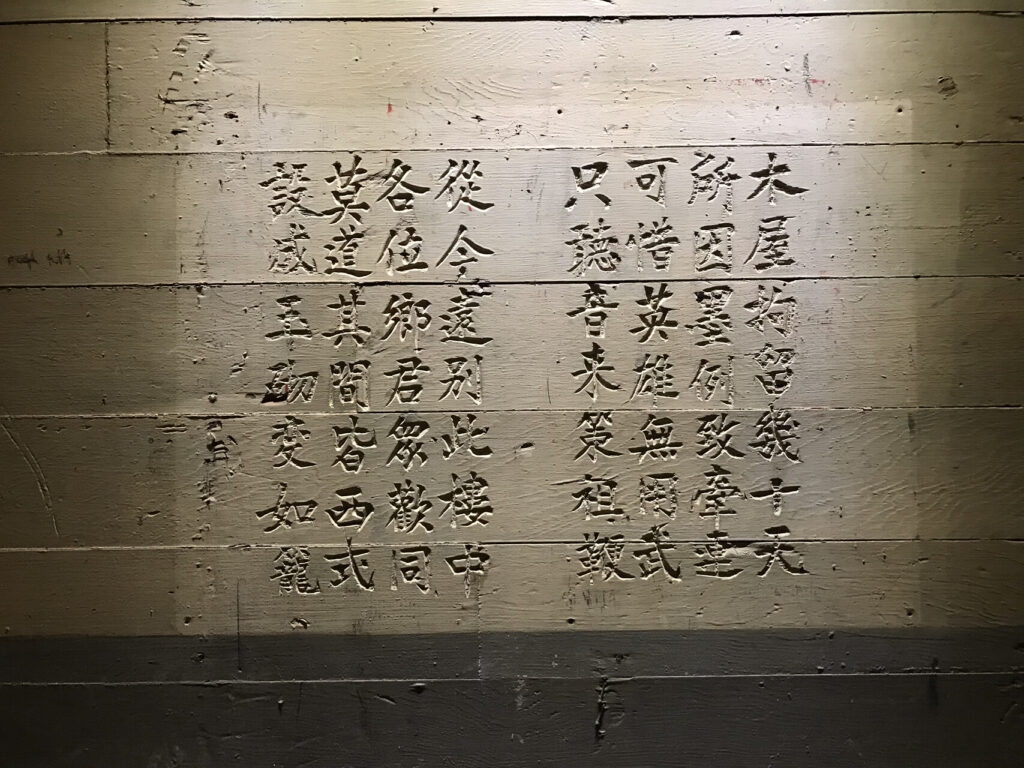

“Detained in this wooden house for several tens of days,

It is all because of the Mexican exclusion law which implicates me.

It’s a pity heroes have no way of exercising their prowess.

I can only await the word so that I can snap Zu’s whip. From now on, I am departing far from this building

All of my fellow villagers are rejoicing with me.

Don’t say that everything within is Western styled.

Even if it is built of jade, it has turned into a cage.” Poem 135, Translation from “Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940.”

The poems are written in Chinese characters (hanzi) in the style of classical Chinese poetry. The poets were primarily Chinese who spoke the Cantonese and Toisanese dialects. Andi explains that the written characters can be translated to have the same meaning regardless of the dialect, but when read aloud in each of them, the sound of the poems is completely different.

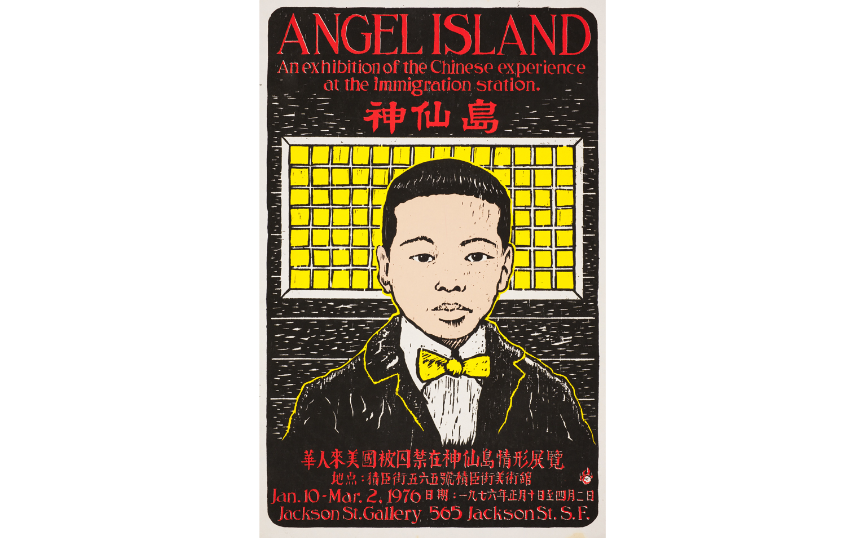

In 1970, Alexander Weiss, a former park ranger on Angel Island, found the forgotten building and alerted his professor at San Francisco State University, George Araki, who identified the carving as poems. Araki gathered friends and family and started together documenting the barracks. This finding sparked a movement in the Chinatown community in San Francisco to protect and document the site, which holds so much of their ancestral memory.

A critical part of community activism in the 1970s was organizing art installations and exhibits as ways to teach people about the history of the Island that couldn’t be found anywhere in a book. Among these creative paths, Genny Lim, Him Mark Lai and Judy Yung (who was Chinatown’s first librarian) researched the history, interviewed former detainees, and translated the Angel Island poems from Chinese into English in “Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-40,” a seminal book first published in 1980.

Nearly 40 years later, composer Huang Ruo was commissioned by the Del Sol Quartet to write an oratorio inspired by the Angel Island poems for the string quartet and chamber choir. “Angel Island: Oratorio for Voices and String Quartet” premiered on Saturday, October 23, in the Angel Island Immigration Station. Andi joined this project with the Del Sol Quartet as a community outreach person. Diving into the Angel Island poems with Katherine Bates, the quartet’s cellist, they were intrigued by a reference to “The Jingwei Bird” in one of the poems.

The Jingwei Bird story is a myth about a woman who drowns in the ocean and is transformed by her grieving father into a bird. Her fate is to fly every day to drop sticks and stones into the ocean to fill it so that no one else goes through the same. This, explains Andi, for Chinese people is a lesson of perseverance in the face of hardship.

“What would this story say to us today? The poet Genny Lim’s interpretation is that the myth is a reflection of our determination to never stop our responsibility to the planet; the sticks and stones are the Jingwei Bird’s aspirations that no one should drown. Can we use the myth to think about our relationship to the sea? After COVID-19 there is a rising of anti-Asian hate that especially Elders are navigating. We are aware of this and thinking about how, for many communities, you get solace when you go to the ocean. What happens when you need to go out and look at the ocean, and it is terrifying? It’s been an exercise to try to think about another way to tell the story and still honor the way it was told.”

Moreover, they have been looking at how the Chinese have used the bay waters because a lot of that history has been erased. Andi shares that memories of difficult migratory journeys often instilled a sense of fear of the power of the ocean, and many people from the same generation as her parents, who spent most of their time working to support their families, didn’t have recreational time to learn to swim. She continues:

“Fear may arise when you have made an ocean crossing, and you are really aware of how small you are when you are at the mercy of nature. But we can use myth, poetry and music to go deeper, to reexamine our own relationship to the ocean, as we recover and preserve the history of the early Chinese immigrants whose contributions have been largely invisible, or even erased.”

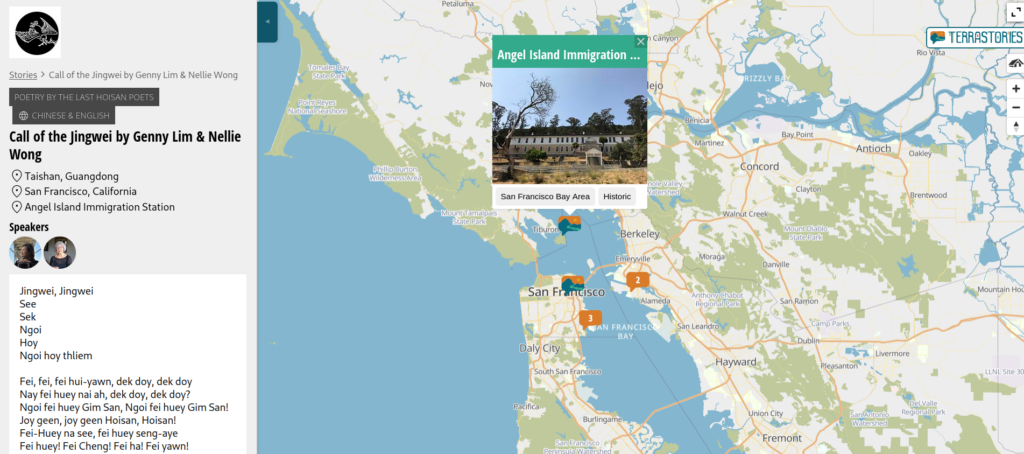

To Andi, the Jingwei Bird story is now just a piece of the broader process that has evolved from collectively diving into Angel Island’s history and the stories carved on its walls. Together with The Last Hoisan Poets (Genny Lim, Nellie Wong, and Flo Oy Wong) and the Del Sol Quartet they use Terrastories as a tool to document and share this process: the connections, relationships, and creative collaborations of people whose family history is related to the journey of this story.

“It’s a beautiful way to think about storytelling. In the old times you would sit around the fire and hear these really long stories and everybody would be transfixed. With Terrastories, instead of adding them to the social media basket, it gives you a better perspective than just reading something, it orients you in time and space. So that’s where the mapping is so valuable.”

The journey of the Jingway Bird story is available in Explore Terrastories through videos, audio clips, and written place-based stories that share the knowledge of the Chinese diaspora while honoring this story that crossed the sea with their ancestors.

Click here to check out this and other place-based stories communities around the world are sharing!

The Angel Island Immigration Station is located on the unceded ancestral lands of the Coast Miwok people of present-day Marin and southern Sonoma counties. We honor with gratitude the land itself, and all of its ancestors: past, present, and emerging.