Waorani: Mapping Ancestral Lands in Ecuador

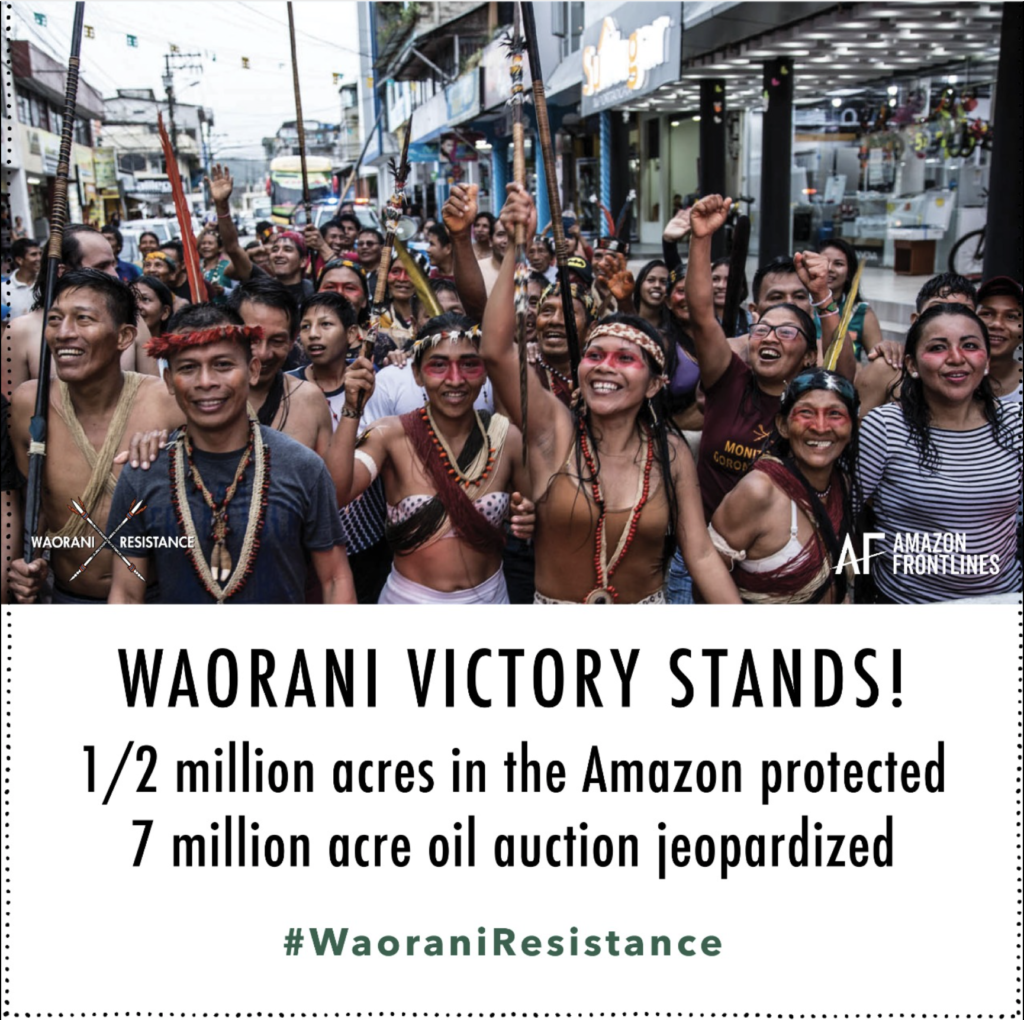

Over the course of four years we partnered closely with the Waorani people of Ecuador to pilot innovative software, Mapeo Desktop, and map their ancestral territory. After 4 years of gathering map data the Waorani won a decisive and historic victory when they won a legal case against the Ecuadorian government and saved half a million acres of Amazonian rainforest from oil drilling.

Who are the Waorani and What are they Defending

The Waorani are an Indigenous people living in the headwaters of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Originally nomadic hunter-gatherers, they started setting up more permanent villages after being contacted by missionaries and oil workers from the 1950s onwards.They effectively fought against different waves of invasion, from the Inca to the Spanish conquistadores, from rubber tappers to American missionaries and oil companies. However, since contact, their territories have been greatly reduced, and their remaining lands are now impacted by logging, oil extraction, and colonist settlement.

Even as Waorani people increasingly interact with national society and the monetary economy, they maintain many customary practices and a deep connection to their territory. Today, most Waorani still depend on their lands, rivers and forests for most of the resources they need to live, from hunting and fishing resources, to medicinal plants and materials for ceremonial items.

The Waorani, whose 6000-strong population now lives in about 50 small villages, have legally recognized rights to much of their ancestral territory in a single land title of nearly one million hectares of rich and megadiverse Amazon rainforest. However the Ecuadorian State retains rights to subsoil resources, including oil and gas, which it can concession to private companies to exploit.

How the Mapping Started

There has been oil extraction within Waorani territory since the 1980s, but the western part, known as the Pastaza region, remains free from oil platforms. However in 2012 the Ecuadorian State created an oil concession, Block 22, covering much of this region. At that time a group of Waorani elders visited other Indigenous territories in Northern Ecuador and witnessed the devastating and ongoing social, environmental and health impacts of decades of oil extraction. The elders returned home and shared their experiences, and their communities determined to prevent similar contamination from impacting their lives and lands.

As a part of their strategy to prevent drilling in their territory the Waorani set about creating “a map full of things that don’t have a price.” They began working with the support of two local partners: Alianza Ceibo, an umbrella coordinating group made up of representatives from four Ecuadorian indigenous peoples, the Kofan, Siekopai, Siona and Waorani, and Amazon Frontlines, an international, multidisciplinary team living and working alongside Alianza Ceibo on a variety of programs from installation of clean water systems to legal defense. A Waorani mapping team was established, and they reached out to Digital Democracy to ask for support to design a methodology.

The Development of Mapeo

The Waorani tested a variety of different mapping tools and applications but none were a good fit for their very remote, offline environment and collaborative process. Digital Democracy had seen similar needs with local partners elsewhere, and had just begun to develop a new, more appropriate piece of software: Mapeo. The Waorani Mapping project became the main pilot use-case for the development of Mapeo, and the team started to use it and contribute to its design in 2015, using it for four years during the mapping of twenty villages.

The Role of Maps and Mapping in the Waorani Land Defense

The Waorani intended the maps to be a tool to communicate their relationship to land and territory to others, and to gain support for their vision. In 2018, this was put to the test when the Ecuadorian government announced a massive sale of new oil blocks that encompassed over 7 million acres of rainforest, including Block 22 – the western part of Waorani territory where the mapping had taken place.

The community decided to launch a legal case against the government to fight the sale, and Amazon Frontlines and Digital Democracy helped them publish an online mapstory showcasing their message for the accompanying campaign. The Waorani map told a different story from that of the government — one that showed their land to be rich in biodiversity and steeped in cultural history, and in which every single vibrant acre of forest in question would be threatened by oil production.

In 2019 the Waorani won the lawsuit when the national court ruled that the Government had not carried out adequate consultation before creating the oil blocks, violating the communities’ rights to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). The oil block was removed and half a million acres of the Amazon were protected. The case set a major precedent for Indigenous action within Ecuador and across the globe.

Although the maps themselves were the physical outcome of the mapping work, and played an important role in the court case, the process of map-making was equally significant. The process included multiple workshops at the village level to discuss the mapping and look at drafts. Over the course of hundreds of miles of footpaths trodden by elders and young people visiting important sites to share and document biocultural knowledge, a rich shared awareness and language relating to territory and the threats to it emerged. This proved critical when the Waorani started preparing for the court case as there was general consensus on actions and strategy needed to defend their land for future generations.

The Waorani Mapping Methods

As of 2020, the Waorani Mapping Team has completed the following process with 20 out of the 52 Waorani villages.

Elements

People: The most significant ‘ingredient’ by far in the mapping was the Waorani people themselves: the deep knowledge and love of territory that they brought to the project and their determination to keep it clean and healthy for the future. The Mapping Team gained expert technical, facilitation and training skills, and worked with as wide a group within each village population as possible to draw territory maps and carry out trips to map ancestral knowledge with a GPS.

Values: The values underlying the project were critical to its success. One of the most important of these was that of autonomy, which guided how the Waorani team started the work in each community, agreeing on all protocols and discussing the methods and clarifying the communities’ role in the ownership of both the project and the knowledge mapped. Supporting community autonomy and sovereignty and local data ownership was also a core value in the development of Mapeo.

Technology:

- Large sheets of paper, colored marker pens

- GPS handheld devices (Garmin etrex, various models)

- Weather-proof notebooks

- A laptop and backup drives

- Lightweight, portable projectors so that an entire village could watch the map editing in real time

- GIS and cartography software: Mapeo Desktop, QGIS, Mapbox Studio

- Design software: Adobe Illustrator

Workshop and Trip Resources

- Boat, fuel and food supplies

- Emergency kit: First Aid Kits including snake antivenom; Satellite phones

- Walking kits, rubber boots, rucksacks, waterproofing etc.

Methodology in each village

Community Agreements: The Waorani mapping team starts by holding a preliminary meeting in each village to ensure understanding about the project and agree upon the conditions and methods of the mapping.

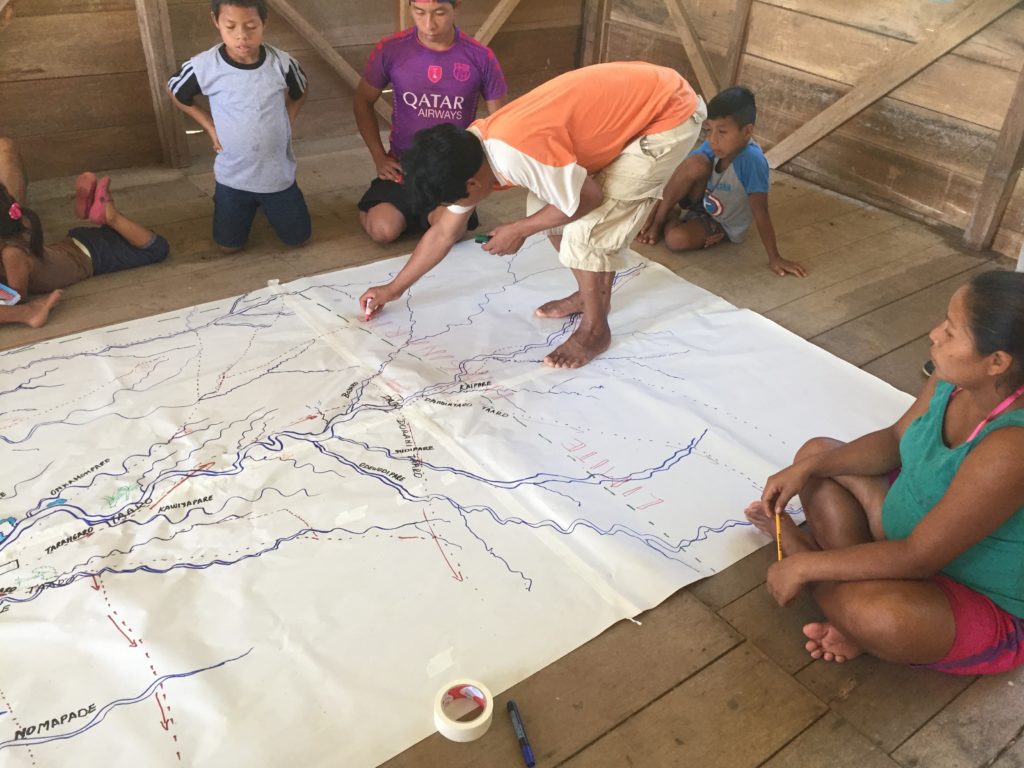

Sketch Mapping: The process begins in a participatory way with paper & markers. Everyone in the community — men, women, elders, children — is invited to come and draw maps of their community lands, marking rivers and streams, hunting and fishing grounds and areas containing important resources across large sheets of paper. Once the paper mapping is complete, the community decides which areas and paths to visit on foot, and makes a plan for the ground truthing based on the paper maps.

Creating a Mapeo Configuration: With the paper maps as a reference, the community decides which features are important to document (eg. waterfalls, hunting grounds etc). A designer works with the Mapping Team to turn these items into unique symbols that will comprise the legend - this process is returned to regularly as each village has some new resource they want to add to the map. The Waorani legend currently contains over 150 items.

GPS Training and Ground truthing: The paper mapping is followed by walks in which village elders and knowledge-holders are joined by a team of young people from the village, trained in GIS and GPS by the core Waorani Mapping Team. They visit important areas, track hunting and other paths to collect stories and GPS points to help digitize the hand-drawn maps.

Data Entry: Back in the village, the team enters the data from the GPS and hand-drawn maps into Mapeo Desktop, as well as additional information and stories. A variety of offline background maps including satellite images, and analyses showing river basins and elevation, are used to help locate geographical features. Once the data points are uploaded, the map is projected onto a wall for the whole community to see.

Export: The data is exported from Mapeo to a GeoJSON file, and then uploaded into Mapbox Studio. The Waorani Team worked with Digital Democracy to create a design template in Mapbox and agree on color schemes and fonts etc. Maptiles of the area relevant to the community are exported to Adobe Illustrator, where a legend and titles are added.

Print: The Mapping Team takes draft maps back to each village for further editing and verification before the final maps are prepared and printed. Each family is given a copy of the map and a larger version is printed for communal use.

Here is a detail from one of the first maps created during the process with the village of Nemonpare:

Just a few of the over 150 icons the Waorani have created over time:

Further reading:

- Our Rivers are not Blue: Lessons, Reflections and Challenges from Waorani Map Making in the Ecuadorian Amazon, Aliya Ryan. Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers (2018)

- “Indigenous Cartography & Decolonizing Mapmaking”, Emily Jacobi. Digital Democracy (June 24, 2020)

- Waorani Interactive Map - Amazon Frontlines & Digital Democracy.

- “‘Our land is not for sale’: Waorani Resistance in Ecuador”, Emily Jacobi. Digital Democracy (May 23, 2018)

- “Maps in Court and the Waorani Victory”, Aliya Ryan. Digital Democracy (May 26, 2019)

- “From spears to maps: the case of Waorani resistance in Ecuador for the defence of their right to prior consultation”, Margherita Scazza and Oswando Nenquimo. International Institute for Environment and Development (2021)

- “Waorani People Win Landmark Legal Victory Against Ecuadorian Government”, Amazon Frontlines (April 26, 2019)

- “Waorani Territorial Mapping” - Opi Nenquimo Magazine of the University of Mexico (July 2018)