ECA-Amarakaeri: Monitoring the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve in Peru

Pour le moment, ce document n'est disponible qu'en anglais et en espagnol. Si vous souhaitez aider à le traduire en français, nous serions ravis de votre contribution!

An intercultural co-management experience between Indigenous Peoples and the Peruvian State

In the Peruvian Madre de Dios department, the Harakbut, Matsiguenka, and Yine Peoples have monitored and protected their ancestral territories for centuries and consider themselves as owners and guards of this part of the Amazon. In 2002, following 18 years of constant struggle, part of their ancestral territory was recognized as a natural protected area, called the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. Since 2006, the reserve is co-managed between ten Indigenous communities (organized by the ECA Amarakaeri organization) and the National Service of Protected Areas (SERNANP), with the support of two Indigenous organizations (FENAMAD and COHARYIMA). The management tool for the monitoring of the reserve includes the use of state-of-the-art technology (such as the app Mapeo and drones) by community guards, park rangers and technicians to protect their ancestral forests from illegal mining and logging. Their exemplary efforts have been recognized by the Equator Prize in 2019. Moreover, the IUCN included the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve in their Green list because of its high conservation status (98.55% of their territory presented a high conservation status in March 2021).

The Harakbut, Yine and Matsiguenka Peoples and their ancestral territories

The Harakbut, Yine, and Matsiguenka are three different Indigenous Peoples that have inhabited the Madre de Dios region in the Peruvian Amazon for thousands of years. Their territory is the basis of their existence as it is the space for their “Vida plena” (full life), which includes all areas where they hunt, fish, cultivate and gather, and where they develop the social and spiritual aspects of their lives. Their ancestral lands host some archaeological remains which illustrate the deep, millennium-long relationship that these Peoples have with the Madre de Dios region.

Despite this, for centuries, their ancestral territories and their rights have been threatened by multiple invasions and aggressions performed by many intruders, including the Incas, the Spanish conquistadors, the rubber barons, the foreign and local gold miners, and the oil companies, among others. For generations, the Harakbut, Yine, and Matsiguenka Peoples have invested their lives in protecting their lands and fighting for their rights. This persists with the current generation, who are now using monitoring tools to preserve their “Vida plena.” Note: The Peruvian government has recognized some but not all of their ancestral territories. According to Thomas Moore’s 2020 article El Pueblo Harakbut, Su Territorio y Sus Vecinos, the sum of titled land by the Peruvian State for the 12 Harakbut, Yine, and Matsiguenka communities living next to the Amarakaeri Reserve only represents 6.7% of their ancestral territory.

Invasion waves: Gold, coca leaves, rubber and hydrocarbons

The ancestral territories of the Harakbut, Yine, and Matsiguenka Peoples already faced threats during the Inca Empire in the form of gold and coca extraction. Invasions continued in the sixteenth century with the incursions of Spanish conquistadors into the Madre de Dios region to extract gold and build coca plantations. In the 1820s, after the Independence of Peru and in an attempt to promote commercial relationships with the US and European countries, colonists from many countries were encouraged to settle in the ancestral lands of local communities and conduct gold mining in Madre de Dios. Waves of invasions related to gold mining continue into the present, and gold mining is still one of the major threats to the Harakbut, Yine, and Matsigenka Peoples and their territories.

During these invasions, local Indigenous Peoples mostly refused to work for the invaders and resisted when these activities encroached onto their territories. The booms and declines of gold and coca demand shaped the elastic border between colonized and Indigenous Peoples’ territories. In the present day, mining rights overlapping Indigenous territories are not permitted without authorization of the Indigenous local communities, however many miners nevertheless have mining rights inside community territories since these laws are not retrospective and those mining concessions obtained before the land titling of Indigenous communities are not affected by them.

In addition to gold mining, Madre de Dios also faced the arrival of rubber barons and traders at the end of the nineteenth century. These inflicted slavery, manhunts, and other forms of systematic brutality towards the local Indigenous communities, causing their populations to experience a major decline. Most Indigenous populations from Madre de Dios refused to work in the rubber camps and decided to hide in the forests and the headwaters of the rivers. Some of them have gone into voluntary isolation, avoiding contact with other societies even into the present day (e.g., the Mashco Piro).

During the same era, Spanish missionaries arrived in the Madre de Dios region and often joined efforts with extractive companies to subjugate and convert local communities, and to establish a well-connected gold mining industry in the area. In the 1950s, SIL International arrived in the region and founded boarding schools that debilitated local languages and cultures.

More recently, in the 20th century oil and gas extraction started in Madre de Dios. Like gold mining, this industry continues to be a threat in the region.

Why the local communities wanted the creation of a protected area

When the process of land titling in Madre de Dios began in the late 1970s, land titles were only offered for the areas where the communities were actually settled, excluding most of their ancestral territories. Far from preventing more threats to their territories, this fragmentation of the territory served as an invitation for many loggers, miners, and cattle companies to exploit the ancestral lands of the Harakbut, Yine and Matsiguenka communities.

In response to this high pressure, in the 1980s the Indigenous communities created a multi-ethnic alliance called Federación Nativa del Río Madre de Dios y Afluentes (or FENAMAD for short) to protect and preserve the ancestral territories of Harakbut domain. Early on in their existence, FENAMAD asked the Peruvian Government for the creation of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve (RCA). After 18 years of struggle and numerous petitions by the organization and upon the exclusion of some territories within the reserve limits due to the presence of mining concessions, in 2002 part of their ancestral territory was categorized as a natural protected area, called the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

The Amarakaeri Communal Reserve currently

The Amarakaeri Communal Reserve covers 402,335.62 hectares of Harakbut, Yine, and Matsiguenka ancestral territories and it is located in one of the biodiversity hotspots worldwide. The reserve protects the headwaters of the rivers Eori/Madre de Dios and Kanere/Colorado, keeping an environmental balance and ensuring the wellbeing of the local communities living in its buffer area.

The management of the reserve is shared between the Indigenous Peoples and the Peruvian State through a special regime for communal reserve and an open-ended administrative contract. This synergy mechanism is called co-management, and it consists of these two main actors working towards the same goal of preserving and protecting the reserve and generating “Vida Plena” (full life) opportunities (sustainable activities) for its partner communities.

In 2006, the Executor of the Administrative Contract of Amarakaeri (or ECA Amarakaeri for short) was declared, and it represents 10 Harakbut, Yine and Matsiguenka communities living in the buffer zone of the reserve. Since then, the reserve is co-managed by these 10 communities and by the Peruvian Government, which is represented by the National Service of Protected Areas (SERNANP). Moreover, all communal reserves in Peru receive support from a national-level representative organization called ANECAP.

Through this mechanism of co-management, community guards, park rangers and technicians of both organizations have been patrolling this area side by side for almost two decades.

The monitoring that we are doing in Amarakaeri is the oldest work that has been done by the communities. It is not an obligation, but rather traditional work that we continue to carry out to this day. -Luis Tayori, leader of ECA Amarakaeri

As a result of these combined efforts and the long history of Indigenous Peoples taking action to protect their lands, the reserve has one of the highest status of conservation worldwide, with 98.55% of its territory showing a good conservation level in March 2021.

Despite the Amarakaeri region being officially defined as a protected area and despite all the efforts of both ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP, the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve still faces many threats and pressures, which include illegal and informal mining, illegal logging, roads, blast fishing, land invasions, and other illegal activities. In one extreme case, the state released an oil concession (Lote 76) to the US company Hunt Oil, which overlapped most of the reserve. (After Hunt Oil conducted some exploration activities in the area, there were some factors that caused the abandonment of the concession by the company, such as two lawsuits filed by local communities, as well as contract and market conditions.)

The co-management team of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve is also implementing the climate action proposal Amazonian Indigenous REDD + (RIA), which helps to communicate the contributions of the reserve to the nationally determined contributions (NDC) through nature-based solution activities. These imply adaptation, mitigation and resilience to the effects of climate change.

The Monitoring Program in Amarakaeri - The use of technological tools

With the creation of the reserve, a monitoring program was set up to monitor the threats and pressures in the reserve and its buffer area, with active collaboration from community guards, park rangers and technicians.

At first, they were using basic tools such as pencil and paper, but digital tools were progressively introduced, and currently state of the art technologies such as smartphone apps and drones are being used, improving the effectiveness of the patrols conducted.

As pressures and threats on the reserve started to increase SERNANP and ECA Amarakaeri designed a monitoring strategy to protect the territory, with the participation of the partner communities and the organizations involved. This management tool includes enhanced collaboration with other institutions and, especially, the use of new technological tools. The implementation of technology emerged from the need to connect ancestral monitoring knowledge with modern scientific knowledge. For this reason, they decided to seek out technological tools that could be useful for the monitoring process.

After trying out various other apps for monitoring, in 2018 ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP decided to introduce the tool Mapeo in the Monitoring Program of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

Mapeo was selected because of its easy access and use via smartphone and because it does not require internet connection for its functioning. Moreover, Indigenous Peoples and SERNANP have participated in its design, and therefore its use and utility respond well to the needs of the reserve. Mapeo enabled the monitoring team to transition from creating physical reports to digital ones, and allowed them to send alerts via Whatsapp and email in real time (when internet was available).

First efforts were oriented towards creating a customized configuration (Fig 1) and an offline base map, as a way to improve the suitability and usefulness of Mapeo to the goals of the monitoring program. Another important step forward during this implementation phase was the increased technical capacities of technicians from both ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP as a result of working with Mapeo.

Currently, Mapeo Mobile is used in the reserve by both ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP to monitor the reserve and collect information of interest directly in the field with a smartphone, without needing internet. Mapeo Desktop is mainly used to centralize all the information, and to visualize and analyze the data.

The innovative and collaborative approach used by ECA Amarakaeri has been recognized with the Equator Prize in 2019, and the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve has been included in the IUCN Green List for its successful and exemplary management model.

Other actions taken

During the almost 20 years that the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve has existed, ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP have taken many actions to preserve and defend their ancestral territories and their “Vida plena” (full life).

Some of these are legal actions triggered by the knowledge and evidence pieces collected during patrols, highlighting the importance and the contributions of the immense work that communal guards, park rangers and technicians are doing.

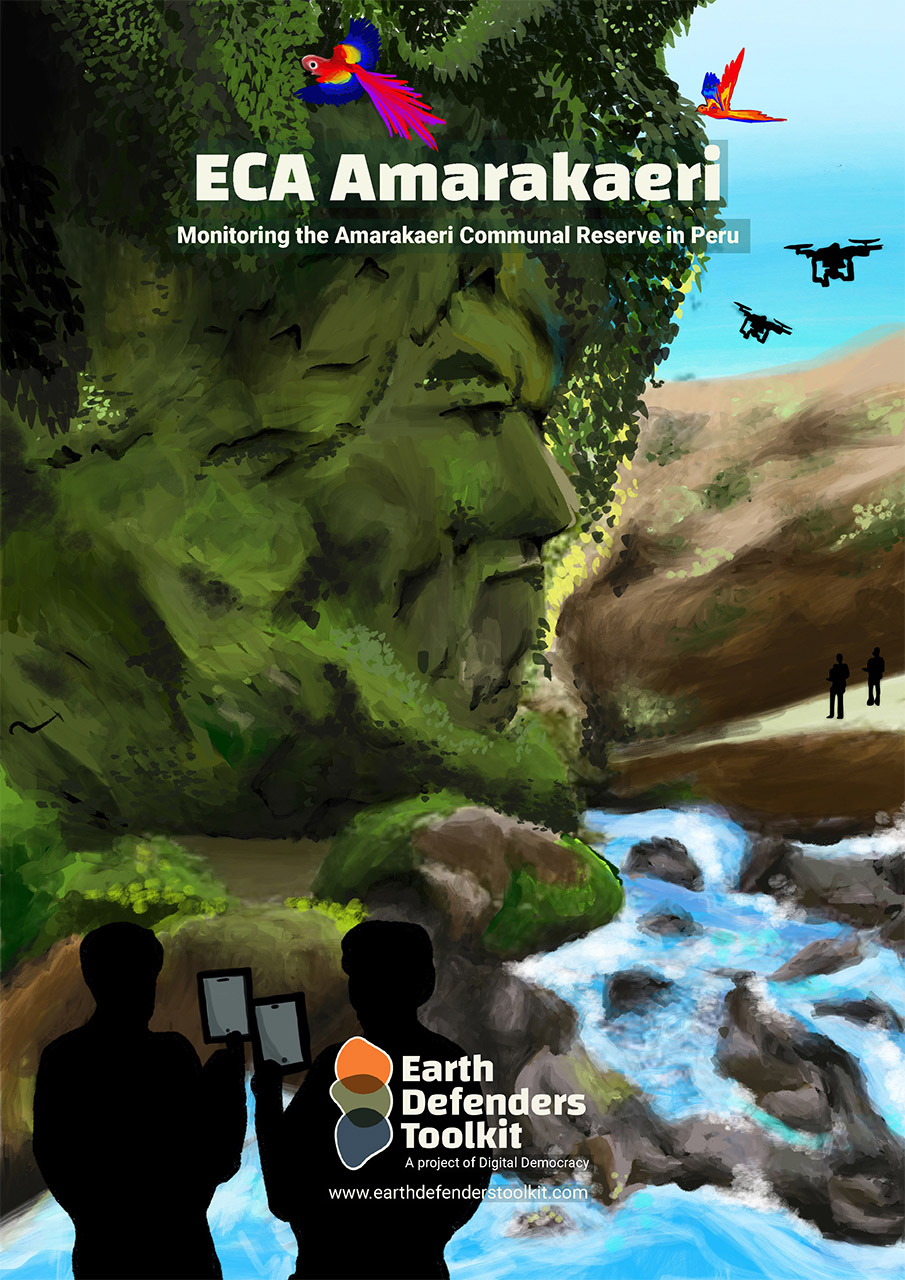

Other actions have had different origins. A very remarkable one is the rediscovery of the Harakbut Face - a legendary and monumental rock with the shape of a face, stories of which were passed down for generations among Harakbut families but its location no longer known – by ECA Amarakaeri. This event happened in 2013, when the US company Hunt oil began exploration activities in a hydrocarbon concession covering most of the reserve. This rediscovery strengthened the position of Indigenous People against hydrocarbon companies, by providing them with another piece of vital evidence that the territory has belonged to them for centuries.

We would like to acknowledge ECA Amarakaeri and the Harakbut, Matsiguenka, and Yine communities for allowing us to share their story and images in this case study.

The Amarakaeri Monitoring Process

As of 2021, all 14 park rangers and 24 communal guards from 10 communities, as well as the leaders and technicians of ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP, are using Mapeo during their patrols and surveillance tasks.

Elements:

People: The current monitoring process is a direct continuation of the traditional monitoring that the Harakbut, Yine and Matsiguenka Peoples have been conducting for centuries to protect their ancestral territory and their “Vida Plena” (full life). Since the creation of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, the park rangers and technicians of SERNANP have joined efforts with those of the local communities to keep this exceptional area clean and safe. Currently, both local communities and the Peruvian Government work hand in hand to patrol and monitor the reserve, its buffer area and the community lands.

Values: This project is grounded in several key values that ensure its success. One of these is the direct and ongoing collaboration between local communities and SERNANP (as well as with other organizations that are providing support). Both actors share non-delegable roles and functions within the framework of the co-management of the reserve, carrying out an intercultural exercise that has three fundamental principles: trust, interculturality and transparency. The respect and consideration of the culture and the ancestral knowledge of the communities are keys to the success of this project. Another important value is the autonomy and self-determination on the part of the communities to decide which information is collected and shared with the Peruvian Government and other actors.

Technology:

- Smartphones with Mapeo Mobile installed - smartphones available for each communal guard, each SERNANP’s control post, as well as for the technicians (mostly Blackview and Samsung models)

- Laptops with Mapeo Desktop installed - coordinator technicians use laptops to manage the data collected with Mapeo Mobile (Asus ZenBook Ultra-Slim Laptop and other models)

- GPS handheld devices (Garmin eTrex)

- Drones

- GIS and cartography software: Mapeo Desktop, QGIS, Mapbox Studio

- Lightweight, portable projectors to conduct training sessions

Workshop and Trip Resources:

- Boats, motorcycles, all-terrain vehicles and other vehicles, fuel and food supplies

- Emergency kit: First Aid Kits including snake antivenom; Satellite phones

- Walking kits, rubber boots, rucksacks, waterproofing etc.

- Printed training materials on Mapeo

- Mapeo files: Installation, configuration and base map files

As of today (June 2021), ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP have compiled more than 150 pieces of evidence of anthropogenic activities (mining, agriculture, illegal activities and logging) with the Mapeo application. From 2018 to April 2021, there have been more than 30 control activities undertaken by the co-management administration of the reserve, including administrative sanctioning processes, judicial processes and eviction processes in the area of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve and its buffer zone. In addition, there have been interventions carried out by other agencies and public administrations, such as the Peruvian Special Environmental Prosecutor's Office (FEMA).

The implementation of Mapeo in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve:

Community Agreements: ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP met with Digital Democracy (Dd) in 2018 within the framework of the project All Eyes in the Amazon to discuss the use of Mapeo by the Monitoring and Security Program of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

Customization of Mapeo - configuration and maps: After multiple meetings between Dd and ECA Amarakaeri focused on sharing what Mapeo is and what the goals and needs of ECA Amarakaeri are, a customized configuration and base map were co-created to better adapt Mapeo to their project.

Training sessions: ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP leaders and technicians were trained in the use of Mapeo and some of them became trainers of the 24 communal guards and 14 park rangers, who are now using Mapeo during their patrols in the reserve and its buffer area.

Development of Mapeo: ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP continuously test Mapeo and offer feedback on how to improve the tool and on which features should be created or improved. With this in mind, Dd develops these features until compiling a pilot version which is then tested by ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP. Their experience and continued feedback on the pilot version helps Dd to continue improving and developing the tool.

Collection of Data: Community guards, park rangers, and technicians are using Mapeo Mobile in their smartphones to collect information during their patrolling tasks in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve and its buffer area. WhatsApp and email alerts are sent to communicate urgent findings to the team of the Monitoring Program of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

Management of Data: Data is collected by an ECA Amarakaeri’s technician, who meets with all the community guards and park rangers and gathers all the information in Mapeo Desktop on a laptop. This process has mostly been done by synchronizing devices but recently they are exploring the use of sync files to conduct a one-way exchange of information.

Use of Data: Data is viewed, examined, and interpreted in Mapeo Desktop. The collected data is used by local decision makers from the communities and from the co-administration of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. Moreover, data is also shared with the headquarters of SERNANP in Lima and other governmental bodies and it is being used to trigger enforcement and legal actions.

Here are the 22 icons that were co-created for the specific configuration that are being used in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve:

Fig 1. Categories co-created by ECA Amarakaeri, SERNANP and Dd for this specific project. Each of them has a corresponding personalized form to collect information of interest for ECA Amarakaeri and SERNANP.

Further reading and viewing:

- Video: “Mapeo: herramienta tecnología para la vigilancia y control de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri” ECA Amarakaeri, SERNANP and Digital Democracy (Feb 17, 2021)

- Blog: “MAPEO: herramienta tecnológica para la vigilancia y control de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri” ECA Amarakaeri (Feb 17, 2021)

- Blog: “Mapeo’s use in guarding Peru’s Amarakaeri Communal Reserve” Digital Democracy (Feb 25, 2021)

- Blog: “Digital Democracy and Coalition Partners Receive Funding to Halt Amazon Deforestation” Digital Democracy (Feb 7, 2017)

- Article: “Natural rockface or tribal sculpture? Peru and US’s Hunt Oil don’t care” David Hill, The Guardian (May 8, 2015)

- Video: The Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, ECA Amarakaeri (May 8, 2021)

- Video: ECA de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri (Peru), Equator Prize 2019 Spotlight Equator Initiative (Oct 10, 2019)

- Video: Rostro Harakbut: Un tótem para salvar la Amazonía Perú Sorprendente (Jul 11, 2017)

- Book chapters: Los Harakbut, su territorio y sus vecinos, Thomas Moore & Madre de Dios en la antigüedad, Thomas Moore, from book: Madre de Dios, refugio de pueblos originarios, Chavarría Mendoza, María C.; Rummenhöller, Klaus; Moore, Thomas, editors (2020) Lima: USAID. 518 pp.

- Book: Indicadores climáticos y fenológicos del pueblo Harakbut – Interpretación de los mundos Harakbut, Luis Tayori Kendero, Klaus Quicque Bolivar y Natividad Quillahuamán Lasteros (2018) Lima

For further information: